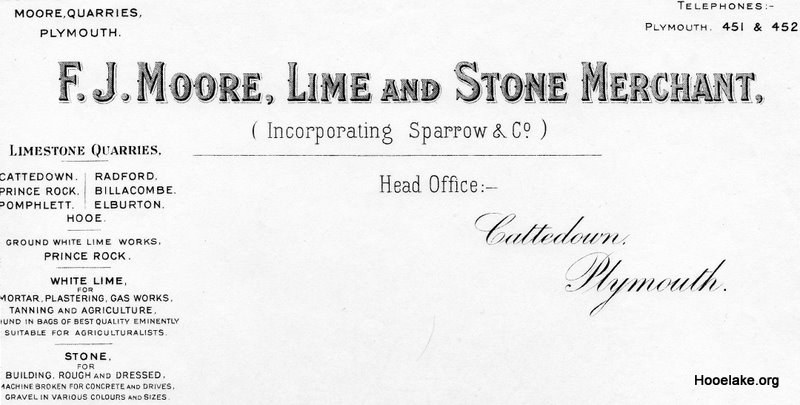

A Little Stonecrete history and the F.J.Moore Quarries Plymouth

These are extracts from a book by Alec Wood who worked for F.J.Moore’s Stoncrete works at Pomphlett. He has written a number of books of his interesting life, his employment and times at Stonecrete, he worked for them prior to World War II as a trainee mould-maker and was later re-employed by them after the war was over. Amongst the pictures supplied I have also incorporated some additional pictures from Alison Hanson of Radford & Hooe Quarry from that period.

Alan Wood, Alec Wood’s son who supplied these extracts continues…

His first book covers his early life being brought up by parents who placed him, his 2 brothers and 3 sisters into a home. His re-married Father moved from the original home to a council house in St.Budeaux, Verna Road where I later spent my early years playing on the rockery. His reminiscences and descriptions of pre-war, and post-war Plymouth are interesting. This first book has references regarding Stonecrete as does the first part of the second book.

I can assure you that all the details regarding his references in the books were very carefully investigated and he even went so far as to fly to the U.K. in his elder years to check and photograph the details before print. The books were only printed in limited quantity as was his wishes. A pair of signed and dedicated to each of the close family therefore only six of each exist.

As an entertaining history of one mans life and life in general pre-war, war and post war in England it is good reading.

The memoirs of Alec Wood – Extract One

…eventually all this became too much for me, or to be more accurate, to my left foot. Marching had become agony and. after a session in hospital, it was decided that I had a permanent stiff joint to my left big toe and was no longer fit for the King’s service, although he did not tell me personally. The unfit, misfit fitter was discharged, I came home to set off in another direction. Four years later, at the outbreak of World War 2, the medical examiners noticed no stiffness to cause any impediment, I was welcomed once more in to the King’s service and again he did not see fit to become personally involved.

Dad must have decided that I should be a tradesman of some sort as my next billet was with F.J.Moore Ltd at their Stoncrete Works at Pomphlett right at the opposite end of Plymouth. Once again, I was not asked my opinion. He took me to an interview where I was shocked to see men, stripped to the waist, shovelling fairly dry concrete into steel boxes mounted on legs, banging steel lids on top until the concrete was packed tight and level, standing on a pedal to force it to the floor to extrude a concrete block on a timber palette and finally running with the block to a stack about five blocks high. Other men were frantically shovelling stone chippings and dust into groaning mixers; others piling blocks on to wheelbarrows and pushing them several miles away to yet more stacks, this time about 10 feet high.

Incidentally, I am tired of translating Imperial measurements into Metric purely for those who have chosen to confine themselves to standards first adopted by an obscure Continental tribe. If you subscribe to this heresy then you should do your own conversions, I shall continue to use the language and measurements which were the foundation of the biggest Empire the world has seen and still would be if they had left well alone.

Block makers, I later learned, were expected to make 450 18x9x4 inch blocks each weighing 40 lbs or 350 18x9x6 inch weighing 60 lbs in an eight hour day at one shilling an hour, or 10 cents. Apart from shovelling and “tamping” the block, it amounts to running 9 tons an average 8ft, or a total of 3 kilometres.

Fortunately, I was not expected to join the slave gang, I was signed as an Apprentice Stone Mason. For many years I considered that this was a rather presumptuous title for someone who basically

put the finishing touches to concrete castings, until I became a Director of a company in Somerset who employed 25 masons doing just that who accepted the title as of right. Admittedly they were producing a remarkably good substitute for natural stone which was beginning to become very expensive. It was sometimes called Artificial Stone, sometimes Reconstructed Stone or even Cast Stone, depending on whether you were buying or selling!

I was expected to attend Plymouth Technical College three evenings a week to study for the National Building Certificate.

A Hercules bicycle now became my very own for the 40 minute trip to and from work and the half an hour journey to Night School. The hire purchase instalments came out of my meagre wages which left me about 10 cents to spend on wine, women and riotous living.

My early work was as a finisher, that is rubbing down concrete products, such as lamp standards, with a carborundum stone to remove casting fins and blemishes, then rubbing in a mixture of cement and stone dust with a rag until all the “blow holes” were filled. Edges and corners were made good with a small, double ended trowel known as a plasterer’s “spoon”. There was a snag, an occupational hazard for which there was no cure available in those days. Very soon my hands and particularly the tips of my fingers, became very tender, the lime in the cement having burned small, bleeding cavities called “bird’s eyes” which became quite painful when the hands dried. Gloves were only useful temporarily as they soon wore out, or at least the woollen or leather variety did, and these were all that were available to us. Thick rubber gloves were useless as they made the hands very soft and, in any case, you could not hold the spoon on any delicate work. Nowadays, the union would have insisted on the employer supplying the type of glove worn by surgeons, but in those more enlightened days, when we were not subjected to the tyranny of trade unions, no such support existed, it never occurred to us that such discomfort was anything more than our lot in life.

By the time that I arrived home, my hands were dry and washing was quite painful. Going to and from work with hands affected by bird’s eyes, particularly in cold weather, was not exactly a joy ride as I could only hold the handlebar grips between the root of the thumb and knuckle, the fingers being fanned out to avoid all contact, all the while praying that brakes would not be needed.

Mid-day dinner was the inevitable pasty warmed in a coal oven in the dining hut by our tea lady. She also brought around our tea cans at ten o’clock “snack time” of ten minutes, taken on the spot. Once again, everyone’s pasty had its own individual shape and form so as to be easily recognisable. After dinner there was just time for a quick game of football or cricket and, for a few months before the firm’s Annual Fete, practice for the tug-of-war team. They trained by tying the rope to a crane standard in the yard. Naturally, they could never pull that over, but it also never pulled them over, nor did anyone for that matter. F.J. Moore owned a number of Grey Limestone and Blue Elvan stone quarries in South Devon so we all joined together for this party which, bearing in mind the piety of the firm’s elders, was to all intents and purposes a Sunday School treat for the workers. FJM also owned whole blocks of Plymouth, especially in the Prince Rock area.

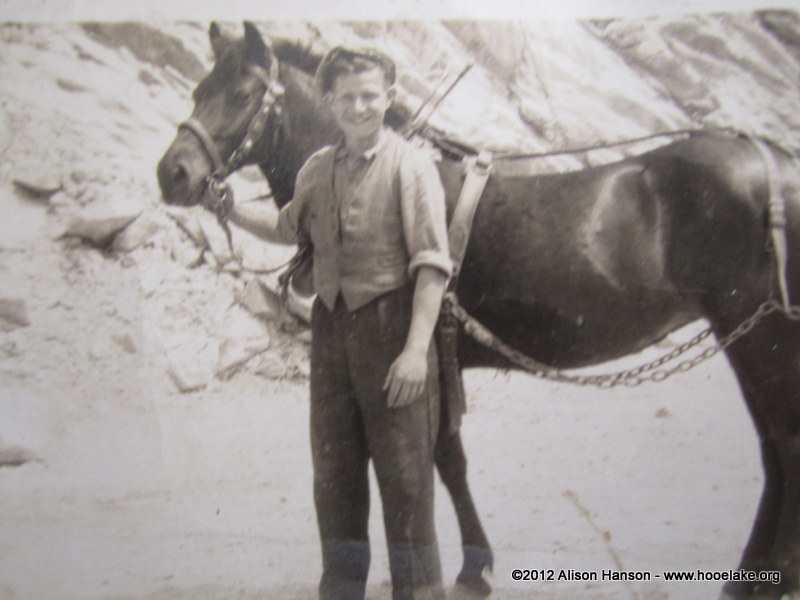

Typical quarry life – Working with the pony to pull the cart full of rocks out of the quarry along tracks. Picture Possibly Hooe or Radford Quarry. Pic. Courtesy Alison Hanson

The Chairman – definitely not Chairperson, a word that would not become necessary for another 50 years which is an affront to the language of our fathers and the dignity of our mothers – the Chairman in my early years was Miss Edith, or “Edie” Moore, a formidable spinster who lived and reputedly owned Elburton just outside Plymouth. The family owned and, indeed, built most of the Methodist Churches for miles around, she was certainly known to Aunt May, she was involved with her Church, Embankment Road Methodist.

Edie did not flaunt her wealth, far from it, such ostentation would have been distinctly unmethodist. She even drove a “Baby” Austin, the Mini of the thirties and whenever she paid a visit to Stoncrete Works it was an apprentice’s job to fill it with petrol from the works pump. This was, of course, pumped in by hand to be rewarded at Christmas with a sixpenny bit with the instruction to share it with the other boys together with the unspoken, but nevertheless clearly implied, instruction that it should not be squandered on riotous living. It was rumoured that her family had prevented her from marrying a naval officer during the First World War and that she became a disillusioned spinster when he was lost in action. He must have been a very unusual Naval Officer as Edie was not from the Munroe mould but more like the Elsie of Coronation Street. Perhaps he was attracted by her money and planned a permanent seagoing command.

The General Manager was one W.G.Cook, the Alf Garnett of Stoncrete. A small, portly man with a raucous London accent, he scorned the use of the compass, or even pointing, when issuing instructions that included position or direction. It was either “Fycing Lunnon” or it was not and was, therefore, unworthy of consideration. He was no fool, being fairly entrepreneurial for his day, although, of course, we did not use such expressions as we had never heard of such odd creatures. With the recent stock exchange collapse many people today are wishing that they, too, enjoyed such carefree innocence. In fact I have read recently that entrepreneur has become a pejorative such as herpes. The “Old man” spoke to me once a year, when he had received my examination results from the Technical College, the rest of the time I was ignored, as it was not usual for persons of his station to acknowledge the existence of lesser mortals and it was difficult to be any lesser than an apprentice.

No word of praise or censure came with my report, so it could be assumed that it was satisfactory. The only acknowledgement was to slow his pace as he was about to pass, an odd shuffling of the feet, then “Gotta bleedin lettah from the Tech, let Mr. Pieper nah what books you need next year!”. Mr. Piper being the bookkeeper, estimator and everything that the Old Man did not handle. Legend had it that some poor idiot could not understand his dreadful cockney accent and queried his “Mr

Pieper”.

“Not bleedin brahn pieper

Not bleedin newspieper

Mr. bleedin Pieper!”

This became part of the Stoncrete folklore. However, they did pay for my books, which was quite extraordinary for those days. These books were standard for the National Building Certificate. Mitchell’s Building Construction Volumes 1 and 2, the Building Mathematics and Building Quantities books were by authors who were no doubt quite competent but were not the revered institution that Mitchell had become in the Building Industry otherwise I would have remembered their names. Then, of course, we had Castle’s Mathematical Tables led by Logarithms which we used for all calculations and which I have already mentioned in my school experiences. These were followed by sines, cosines, tangents, cotangents together with their logarithms plus a host of other tables obviously not often used or I would remember them. I often envied my brother Ron who, as a prize for Maths, won a massive hard cover copy of Castle’s Seven Figure Mathematical Tables – mine were merely four figures in a soft cover.

This probably summed up our comparative abilities, he was a seven figure man, I was a mere four figure, him a hard cover, me a soft cover. In later years Ron was reputed to be able to solve the Daily Mirror Algebra Puzzle on the way to work on the bus and complete the Daily Telegraph Crossword Puzzle on the way home. I say complete as he probably had a glance during his lunch hour.

Which brings me to another of those now useless facts which still persist in the filing cabinet of the human mind despite having last used it 45 years ago in the drawing office, such as it was, after the war. Everyone knows the value of pi – don’t they?. But how many remember log pi (the logarithm of 3.142) as 0.4972? By that time even the slide rule had not eliminated logarithms, it took the adding machine and finally the computer to deal the death blow.

The Works Manager was the Old Man’s eldest son, Bill Cook, a tall, strong man who was only slightly less cockney than his father. Single handedly, he made all the timber, plaster and concrete moulds as well as running the place with a rod of iron. I still shudder with embarrassment at two incidents when he reduced me to a quivering wretch.

The first was early morning on my way to work, bearing in mind that Stoncrete was at the end of a quarry which was still being worked. I cycled through the arch at the entrance, ignored the chap standing in the middle of the road waving a red flag and frantically puffing away at an odd silver like cigarette, my mind, as usual, everywhere but at Pomphlett. Suddenly there were a series of explosions followed by huge pieces of rock flying past only just at my rear. Bill was close behind me and saw everything. He asked me if I had seen the Blasting Sentry and heard the whistle. I said yes to the first and no to the second.

Somehow he felt that it was remiss of me, he drew my attention to the fact that I was required by law to stop until blasting was complete as I might have been hurt. He elaborated on this theme at great length using words that no 16 year old could possibly comprehend, his voice gradually rising to a screaming crescendo, his normally ruddy complexion turning almost purple. It was months before he could compose himself to speak to me directly, instructions were relayed through intermediaries.

The other incident occurred on one Armistice Day, November 11th. At 11 am., the exact time of the cease fire that marked the end of the World War 1, the entire country came to a standstill for two minutes silence. I was busy on my knees “rubbing in” a big stone slab, day dreaming as usual so did not hear the whistle blow. After a while it suddenly struck me that all was quiet, no mixers groaning, no machines vibrating, no hammers jabbering – nothing. I looked up to see Bill standing outside his office at attention and looking straight at me. I scrambled miserably to my feet awaiting the inevitable retribution. After the all clear he walked over to me, stopping a few yards away. He said nothing, he simply looked at me with a contemptuous loathing to convey his feelings that I had failed my responsibility to acknowledge the sacrifice of a million British lives that I might live in freedom.

In spite of all this, towards the end of my apprenticeship he used me to help with his timber, plaster, gelatine and concrete moulds, in fact he often left me on my own.

Bill did make one mistake which was to haunt him for the rest of his days, he married Blondie. A short, plump, voluptuous blond, always heavily made up, she was originally a bus conductor on a small private service that ran between Oreston and Plymouth. Her reputation, before she met Bill was often discussed among the men, it was considered inevitable that he should, as he did, spend every evening at the Plymstock Club playing snooker and gaining an awesome reputation for sinking prodigious quantities of beer. They had no children, which could have meant all sorts of things, but if they had it would have offered yet another interesting exercise in genetics.

Another of Bill’s tasks was to drive his father when the Old Man needed to visit a building site or contractor’s office, using the works only car, a small, grey Standard 8 Saloon. The Old Man could not, or more probably, would not, drive himself, as it would have been beneath his dignity. Just imagine him taking lessons or even taking a test!

In those pre war days, just after the dreadful depression of the early Thirties, jobs were still hard to find but even the tyranny of the block machines or stackyard was preferable to unemployment. To be on the dole was still a disgrace, it was degrading for a grown man to have to grovel to some public servant behind the grill at the Labour Exchange. Of course, most men were too proud to actually grovel, but it must have felt as if they had been forced by a cruel stroke of fate to adopt some sort of penitential posture such was the ignominy attached to the crime of “being on the dole”.

If Bill decided that he needed another man he would phone the Labour Exchange for, say, ten men who would arrive in dribs and drabs, walking or on bicycle. He would select a few, put them on trial to sack all but one at the end of the day. There was a cynical inevitability about this procedure, the one man who survived was not only grateful, he was the fittest and strongest so usually lasted. On the other hand, I cannot recall Bill ever standing any man off, he sacked one or two for various misdemeanours, but, provided that you were prepared to work to his standards you were safe. This sort of feudalism was still the practice in much of England and, although we sometimes questioned the morality of the Moore’s intense Christian beliefs with the way they allowed their employees to be exploited, no one was very surprised and, what is even more surprising, no one really resented such hypocrisy.

Before we leave Bill Cook, I must mention a popular song of the day, American, of course, which started

“Looka, looka, lookee

Here comes Cookie

Walking down the street!”

Now, isn’t that really beautiful poetry ?

The point is that the lads would whistle this tune as a warning when Bill left his workshop, so that everyone would be at their most diligent. It was often enough to shake me out of my usual dreamworld.

The foreman was Tom Moore, no relation of the owner’s family. A retired Naval Chief Petty Officer, he was responsible for all the more important casting jobs as well as collecting the “tallies” at the end of the day. He would tour the whole works in his busy, shuffling gait to enter each man’s production and the number of buckets of cement used in his book to be handed in to the office to be analysed. A kind man, with a wicked sense of humour from many years of lower deck experience, he was always willing to help but at the same time wore an air of cynical resignation at the apparent futility of a system that found him in his present position. Here was another man who completely refuted the common view of the sailor being a drunken slob. He was well spoken, almost cultured and obviously well read, I wonder if there was a past hidden away which accounted for the cynicism that seemed to dominate his attitude?.

The men I remember with affection and respect. Sammy Symons, the main mixer driver for the block makers was a big ex soldier of the Devonshire Regiment who by then had developed a rounded back from pushing a wheelbarrow up an inclined board “run” and lifting the load to tip it into the mixer. The sequence began at the bottom of the run, fill the barrow with a shovel worn to a bright polish with stone dust and small chippings with the prescribed number of shovel loads of each, the load finishing heaped well over the top. Now back to the mixer, discharge the previous mix by turning the big handle at the side. Back to the bottom of the run, lift and push the heaped barrow to the lip of the mixer then lift again to tip the load into the open machine. A bucket of cement from a bin at the side, two buckets of water from a small tank and then start all over again.

Picture from late 1940’s or 50’s of Radford/Hooe quarry worker (Caleb Jnr.) with a generator which he was in charge of operating. Pic. Courtesy Alison Hanson

This went on non stop for nearly 8 hours, the last 15 minutes was allowed to clean the mixer, smashing off the hardened concrete with a club hammer then hosing down. Bill would hear from his workshop if there was the slightest interruption to the groaning rhythm of the mixers, he would be there in an instant to ascertain the reason for the loss in production.

Fred Alford was the king of the blockmakers. A big, strong, swaggering, apparently arrogant man with a strangely kindly, thoughtful and considerate manner of speaking, nothing seemed to be beyond his strength or endurance. Always the first to finish his “tally”, he would wander around the works, help someone to lift a particularly heavy lintel, run out blocks for a man who was behind, all the time challenging Bill Cook to question him. Bill knew that he had met his match and that he was, in fact, priceless.

Then there was Cecil Hurst, a small but strong man with an endless repertoire of filthy stories, he was a wizard with a trowel. There was no man who could approach his skill with cast stone which was always made “semi dry”, that is with just enough water to hydrate the cement but still dry enough to allow the mould to be struck to trowel or float the sides and top to a perfect finish. Moulded units such as sills or cornices only required a template cut to the cross section at each end of the mould with a backboard and front board, all the intricacies were produced by screed and trowel. Legend had it that there had been a man called “Taffy” who was even better than Cecil. Unfortunately, he lost a foot when trying to kick start a mixer, I will not bore you with the engineering details which sometimes required a man to stand on the edge of a mixer and kick the blades to start them spinning.

As with every group of men, there was one dog of a man. Our Bete Noir was Cecil’s brother, Harry. An Ex-Marine, he had the typical cocky arrogance that some short men adopt as a counter to their lack of height. He also felt that he had a sense of humour that needed an anvil to hammer it into shape. Unfortunately, I was often the anvil on which his sarcasm was tempered.

Albert Skelton was another good worker and, unusual with the older men, unmarried. He was also strong and untiring but a kind and very conscientious man at the same time. He spent his time between making lintols of all sizes and lengths alternating with operating the crusher. The sole purpose of this plant was to crush clinker from the Gas Works down to the required size for breeze blocks used on internal walls of buildings for lightness and also for ease of driving in nails for fixings. The crusher was driven by a big Tangye gas engine, something like the single cylinder steam engine of the old days. To start this engine first thing in the morning, Albert would remove the big spark plug from the cylinder, heat it over the canteen stove, dash back, bolt it into position and we boys would swing on the huge flywheel to put the brute in motion. After a few minutes the engine would wheeze and a few more minutes produce a cough and eventually a steady chug, chug. The place reeked of gas but Albert assured us that it was quite harmless as long as the doors were left open.

Last, but certainly not least was young Albert Koch. A lightly built boy about my own age, he had a tremendous sense of humour and we became great friends. He lived quite close to the works in Oreston with his mother, a widow, and I often went to his home. He made no secret of the fact that his father had been German, with his name it would have been difficult anyway. Albert turned this to his own advantage by making it the source of endless jokes, but one that always reduced us to helpless tears of laughter and can be used in all sorts of situations – rather like the Actress and the Bishop. This particular phrase was the one used by comedian Cyril Fletcher, the Goon and Monty Python of the thirties. In Cyril’s parody of Charles Laughton as Captain Bligh of “Mutiny on the Bounty”, Laughton is saying – and you must use his slightly low pitched haughty upper class English –

“Oh! Calamity, Calamity, Causing all this Mutiny!”

The voice should drop a note at the end of the second calamity and at the end of Mutiny. Try it the next time someone is in trouble, it should cure their blues.

I enjoyed the Technical College work, particularly the Architecture Classes. The classical stonework mouldings were a joy, for instance we learned the method of setting out the entasis of a column. A long column tapering slightly from a broad base would appear to be concave unless it were deliberately made convex when it would appear to be perfectly straight to the eye. There was a method of setting out this curve to achieve perfection. All mouldings to the various classical orders have a set geometric form and this, at least, came in useful after the War when much of Plymouth was rebuilt as a consequence of the severe bombing it suffered. However much of the work we did on other things, such as sash windows, literally went out of the aluminium window as the old crafts died.

One craft that died a miserable and far too early death was the use of Duodecimals in calculating Building Quantities. Now there were 12 inches to the Imperial foot and 12 pence to one shilling so a system using 12 as a base was developed. For instance, to calculate the cost of a beam measured in feet and inches at a cost of so many shillings and pence per foot you simply used duodecimals rather than submit to the metric madness introduced by the French simply because they were sore after we walloped Napoleon and exiled him to the Isle of Elba.

Let us say that we have a beam nine foot six and threequarters inches long made of oak costing three shillings and twopence per foot.

On the first line below, the first figure, 9, is known as a “prime”. The second figure, 6, for six inches is known as a “first” and written thus

6. The third figure, 9, represents three-quarters or nine twelfths of an inch and is known as a second and written thus 9.

The second line is so obvious that I should not be wasting your and my time. Three shillings and two pence are 3 primes and two firsts. The third line, where you have to multiply 2 by 9 becomes 18 thirds and written as 1 6

9 6 9

3 2

1 7 1 6

28 8 3

30 3 4 6

= Thirty shillings and three pence.

Or, one pound, ten shillings and three pence.

Being generous, we have made a present of the 4 6, which is actually three-eighths of a penny, although if you wanted to be bitchy or a Quantity Surveyor of the thirties, you could include it in the last column of your Bill of Quantities and then add them all up.

An eighth of an inch was written 0 0′ 1 6 an eminently sensible way of expressing oneself. Before you dismiss this as the ranting of a silly old fool, what about a third of an inch? Simple, just 0’4″ not .33333333333.

Before we leave F.J.Moore, I am reminded of something that only happened during my first year. This was the last time that cement came by sea, from one of the Kent works, I believe. The ship berthed at Pomphlett Quay, the bags of cement then carted to the works by Steam Foden Trucks, that is, trucks from the Foden Works with coal fire, boiler, long brass topped funnel and driven by a steam engine. They had solid rubber tyres and were quite powerful, no hill bothered them but they were painfully slow.

The significance of all this was that the bags were 2cwt bags, twice the weight of the standard hundredweight bag, that is 224 pounds or just over 100 kg and the cement was generally loaded hot at the works and retained its heat in the hold of the ship. The boys’ job would be to push and slide the bags off the truck on to the men’s backs which would be bent and raw at the end of the day. Everyone was involved until the ship was unloaded. I do believe that the Fodens became redundant when a cement works was opened in Plymouth and the bags were a mere one hundredweight. Well, 50 kilograms, is that better?.

The memoirs of Alec Wood – Extract Two

…again with F.J.Moore after nearly 6 1/2 years absence, I was agreeably surprised to be put into the mould shop, now largely producing timber moulds for the precast concrete side of the business. Pre-war, Bill Cook, the foreman and the Manager’s eldest son reined alone and supreme in the Mould Shop and there is no doubt that he was gifted. He rarely set anything out on paper, everything was set out full size on long 9 x 1.5 inch boards, all stacked in one corner – his filing system. In this manner Bill and his father designed and produced a very attractive precast concrete post and panel building system with friezes, gutters and base course which was an extension of the pre-war police boxes we produced and built all over Devon and Cornwall. We even made the plaster board panels for the internal linings. A large prototype bungalow was built on a pleasant spot behind the works overlooking a river and the Elburton Road. It came as no surprise to find that the Old Man moved in when the job was complete..

The point that I set out to make was that it was all set out on these boards and it worked, it all fitted snugly and looked very good indeed. Mind you, they never sold any “Stoncrete Bungalows” and I sometimes wonder if it was not a neat scam to provide a very nice home for the Old Man. Incidentally, cycling from St Budeaux to Pomphlett lasted until the chore of nearly an hour’s ride each way, especially during the winter after a day’s work with overtime, had worn thin. I thankfully reverted to Plymouth Corporation Buses.

Bill Cook rarely used the mould shop after the war. He now concentrated on running the works as the Old Man was drawing towards retiring age. In concrete in particular and building in general, Bill was an undisputed genius. At the bench he was lightning fast and uncannily accurate, in the works he was on top of everything. No machine or vehicle had any mysteries for him, it was said that he only had to approach a recalcitrant petrol driven mixer or gas engine for it to burst into life and practically purr. His manner to the men had mellowed, though not to the extent of inviting familiarity. During the war he had distinguished himself, or so we were continually being led to believe, as leader of an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) Rescue Squad during the heavy bombing raids on Plymouth. This I could well believe, as a practical man, he had no equal. I had the suspicion that these often repeated ARP exploits were to cover any guilt feelings about being in a reserved occupation during the war.

Steve Holberton, a small, stocky, but very active man in his early sixties, spent much of his time in the mould shop. A Shipwright by trade, he was one of the old school of craftsman to become almost a father figure to me. I had much to thank him for, he willingly taught me all the wrinkles of joinery without questioning my right to the knowledge that he had earned through a long apprenticeship and many years of applying his craft. He was nominally in charge of maintenance work to Miss Moore’s property and quarry plants all over Prince Rock and Elburton although another carpenter did most of the work. Steve only went out in those days when it was considered that the job was a little too subtle for Sid, the other chippy, who had the reputation of getting things done quickly with a minimum of finesse. Sid was what was known as a hammer and axe man.

Incidentally, Miss Moore (you will, of course, remember Edie from the pre-war chapter) was still Managing Director of the group whose quarries all over South Devon were really booming. She had reluctantly acknowledged her pre-eminence in the business community of Devon by replacing her Baby Austin car with an Austin 10 saloon which must have set the firm back several hundred pounds. This reckless squandering of the firm’s hard won assets coupled with the fact they she was well over 70 years of age had made it imperative that her nephew, Jimmy Moore, having returned from the Navy, should take over as soon as possible. Actually, it took another couple of years hard apprenticeship before he did take over and, even then, we were not particularly impressed.

To return to dear old Steve. For many years I used a shipwright’s adze given to me by Steve as a dibbock, or digging tool in the garden. An adze has a heavy, chisel like blade fitted at right angles to a wooden shaft, rather like a pickaxe. The blade was curved inwards slightly and the technique was to secure a piece of timber between the feet and swing the adze down to chip or shave the timber to shape. By this means, the curved timbers to a ship or boat could be shaped, Steve could produce the most difficult curves with almost effortless ease.

Dinner, or lunch as it is known these days since even the great unwashed have assumed the form taken by the upper echelons of society – was often a pasty or perhaps part of the family’s dinner of the previous day. This would be warmed up by yet another Edie, the works can lady who had succeeded the can boy of pre-war days. She also brought around our our tea cans at ten o’clock every morning for the ten minute – timed to the second, controlled by Foreman Tom Moore’s whistle – morning break. Now, this Edie was a character, totally different from the slow, stooping, plump Edie Moore. This Edie was also short and rounded, almost barrel like, she was half her senior’s age, she was irrepressibly happy and energetic being the archetypal Plymouthian. Her accent was, by the middle class standards of the day, “common”, her limited vocabulary restricted her to communicating in earthy euphemisms such as “Her’s a dirty cat, her is!”

To become yet another legendary phrase at Stoncrete Works.

The memoirs of Alec Wood – Extract Three

Bill Cook decided that we should enter the twentieth century when another of his inspired decisions was largely responsible for the arrival in the mould shop of a new Universal Woodworker, built by Cooksley. I have never seen another such machine which combined a 24 inch circular saw bench, an 18 inch overhand planer and thicknesser which could handle boards on edge down to 12 inches deep, plus a spindle moulder with a Whitehead Safety Block. All Universals have most of these functions, but none have succeeded in combining the four essentials at such high capability as the Cooksley.

In order to understand this machine, I called in to the Public Library in Tavistock Road on my way home from work to collect a whole series of books on the subject of woodworking machinery. Eventually I could even claim some proficiency as a Saw Doctor, for, in addition to the mundane task of sharpening teeth and deepening their gullets, I learnt the hard way how to set the teeth by bending or hammering each tooth on a shaped block so that they were offset on different sides. The true Saw Doctor tends to treat the mysteries of tempering a distorted saw, especially after overheating, as commonplace. It took me some time together with a few ruined blades before I could save a saw for a few more runs.

Eventually, of course, we went the way of all flesh when a contractor collected them regularly. Similarly, the two 18 inch blades to the planer required regular grinding, sharpening and setting accurately in balance on the cylindrical blocks. We cut and shaped our own cutters for the spindle moulder, the stock moulding was 0.5 inch diameter rods used as dowels, the standard method we adopted for securing detachable sides to our timber moulds for precast concrete.

To illustrate the problems of production in those early post war days, let me tell the story of our Saturday afternoon overtime task. For timber moulds, we preferred redwood, an imported pine from North America and Canada, but imports were strictly controlled as the country could not buy, beg, borrow or steal anything not absolutely vital. Bill Cook discovered a number of 14 inch square baulks of Columbian Pine which had been underwater for some time in the upper reaches of the River Plym. These baulks were well over 40 feet long, we cut them in half and got them back to Stoncrete somehow, but they stank of stagnant river mud for some time. Columbian Pine is a hard, coarse softwood, if that makes any sense, the knots in particular were as hard as brass, consequently, reducing these baulks to 1.5 inch boards presented us and the Cooksley with problems with which it was certainly not designed to handle.

We rigged up roller conveyors each end of the saw-bench and set to work every Saturday after our dinner break to produce enough 1.5 and 2 inch boards to last at least one week. Now, a 24 inch circular saw has about 11 inches above the saw-bench while our baulks were 14 inches deep, so we had to make one run, turn the baulk through 180 degrees, heave the baulk to the front of the saw to cut through the remaining 3 or 4 inches.

Two, or at the most three of these runs reduced the saw to a blunt, overheated bludgeon, the saw’s motor to groaning almost to a stop with the belt from motor to saw about to spin off the counter-shaft. It fell to one of us, mostly me, to spend the whole afternoon sharpening, setting, cooling and cajoling buckling saws, barely managing to keep up to the struggling sawyers. Four hours later, we stank of stagnant mud and itched from the sharp, hard “dust” and splinters which got under our sweat sodden clothes so easily. Later, it was the turn of the planer blades to take punishment from the newly cut boards which did, however, have one advantage over the more reasonable redwood, they never warped, split, or rather “shook” to be precise.

When I became more proficient with the woodworker, Steve and I used to race each other to “shoot” one edge of a 9 x 1.5 or 2 inch board straight – me on the overhand planer and Steve by hand using his traditional 4 foot long wooden jointing plane. It was touch and go most times. I can see Steve now, cloth cap pulled tight over damp brow, his old fashioned wire rimmed spectacles on end of nose, pipe clenched tight in mouth, bulging eyes moist with concentration and the smoke of Condor Tobacco. A nip off here and there, then back for a full run along the whole length of the board, a quick sighting, then a final triumphant run to produce a continuous shaving curling from the top of the plane. I used much the same technique on the machine, but upside down, to offer the shot edge travelling over the top of the planer. We would then place my board on top of his, matching each “shot” edge to look for any tell tale light between the boards.

Retiring from the Quarry, presented with seems to be some sort of heater! Pic. Courtesy Alison Hanson

Somehow I also became responsible for the maintenance and repair of the works plant and machinery. This came about by way of yet another post-war shortage in round mild steel reinforcing bars for reinforced concrete. We were successful with a contract for thousands of concrete clothes line posts for Plymouth City Council, part of their programme for updating existing Council estates as well as building new in the wake of the bombing in 1941 and 1942. Each house was to be provided with two of these 14 foot long posts, but the only reinforcing bars available were a mere 10 feet long. As each post required four bars, one in each corner as it were, it was resolved that each third bar should be cut in half and the 5 foot bar be lap welded with a 10 foot bar over a length of one foot. Have you got the picture?

We acquired a semi portable welding set and once more I was at the Public Library, this time for books on welding. Saturday afternoons were then spent entirely on my own, welding enough bars for the following week’s production. From bars, I graduated to welding broken machine parts, then hard facing concrete mixer blades to lessen wear by using special welding rods. It was hardly a quantum leap to oxy-acetylene welding for thin plate and the like, then a sideways jump to replacing gears, repairing belts on crushers until I became the maintenance dogsbody. This assured me of plenty of overtime and, of course, the money, which, I have to admit was the prime motive behind my sudden driving ambition and thirst for knowledge.

Stoncrete’s two concrete brick presses often gave me the opportunity for a few hours extra and yet a few more shillings in a gluttonous pay packet. Before and during the war these presses worked flat out to produce 14,000 bricks each day using Blue Elvan Limestone dust to provide the high strength required for engineering bricks. The stone, naturally, came from one of our quarries being a dark green variety of basalt, to put you into complete confusion I might add that we often used it when making Reconstructed or Artificial Granite.

With thanks to Alan wood for providing this insight in to quarry life in a bygone era.

Thanks also to Alison Hanson for additional ‘quarry life’ pictures.

You may also be interested in the following posts:-

Alison Hanson’s pictures from Oreston during that period.

F.J. MOORE LIME & QUARRY MERCHANTS

We would love to hear your thoughts and comments on this article. Please post them below.

If you have similar local stories or photos please let us know

Category: History, Personal Accounts

Hello!

My name is Harriet and I, along with a few colleagues, are carrying out some research for Radford Quarry History Project.

We would love to chat to anyone who has memories and/or connections with Radford Quarry.

If you can help at all, please do get in touch via email: radfordquarry21@gmail.com

Many thanks in advance

Harriet

My Grandfather was William George Cook and my uncle was Bill Cook. I remember as a child being taken around the stonecrete works and being fascinated by the machines and equipment. I love Alec Wood’s reference to my grandfather being “the Alf Garnet of stonecrete”, must have been because he was a Cockney. It was most interesting reading these memoirs and I would love to buy a copy if one is available.

Hi, my nan’s (Margaret Combe) uncle was Albert Koch. So her grandad was the German Albert Koch. I have always been keen to find out more about my German ancestry. I know that Albert Koch died young of a heart condition. I have some great photos of him including his wedding day, but unfortunately do not know who the others are in the photo.

I lived in a cottage over the top of this quarry, dad mac McCarthy worked in the quarry. 1949-1955 time

I went to work at stonecrete in 1966 Bill Cook was the boss.I remember that Mr Piper had a limp and Edie was our tea lady. Cecil Hurst was sill working there I remember a few names Reg Coniam Mick Mcmanus My wife’s uncle Bill Beer worked there and Jeff Gale.My job was making bocks on the bock machine and driving the fork trucks.My wife’s father worked for F.J.Moore Charlie Beer.

Is it possible to buy or obtain a copy of this book?

My Father in Law Kenneth Lang worked as a block maker in Stonecrete quarry and progressed to running several quarries (including Venn quarry at Brixham), he died at an early age some 50 years ago working for ECC. We cannot see him on the photo with the buses taken in 1939, but he would have been 17/18 at the time and had worked there for some years already. Anyone with any information on him please contact us as we would love to hear about him.

My mother ‘s father ‘Reginald Babb’ worked for many years as a manager at Moores, not sure which site exactly. He became quite close to Miss Moore, and when they were bombed out of their house for the second time in ’41, Miss Moore allowed him and my mum’s family to live in the office for many months while they sorted out new accommodation.

thank you for a fascinating article, really enjoyed reading this. I have since discovered my 3 photos in this are of Hooe Quarry, with my great uncle Caleb Carder in them. He’s in his late 90s now and still with us, bless him!.

My mother was jean Hawkins, she was miss moore’s secretary at Hamilton house. I can still remember going there and being presented to miss moore. Is there any trace of the pictures that were on the wall upstairs of their barges, EMM,PHE and Triumph? I heard that one of them was loaded with stone and sunk between Drakes island and Mt Edgecombe.